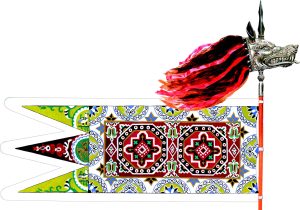

The Kazakh khanate, like any other state, had a well-developed banner complex, which today is being restored by specialists. The most important sources are rock paintings, folklore data, information from travellers and ethnographers from the pre-revolutionary period. According to various information, Kazakhs possessed white (“Abylaidyñ aq tuy”), red and green banners, as well as “ala-shūbar tu” (flaming banner) and “kök-ala tu” (blue coloured banner). Historians believe that the whole flag complex of Kazakhs goes back to the ancient Turkic traditions, and the oldest ones are bunchuks and tugs, i.e. a pole to which the tail of a horse is attached.Among different Turkic peoples the number of tails on the tug could vary, but most often nine were drawn, a sacred figure in the understanding of the Turks and Mongols – a personification of the ultimacy of ultimacy. The horse itself is a mediator between worlds in the memory of nomads, and Mongols used the tails of a white yak – a symbol of power. One should also remember the semantic meaning of the hair and fur of the animals, which in nomadic culture symbolized quantity, wealth and abundance. The bunchuk, the banner with nine tails, was generally owned by the most powerful khans. It was believed that after death, the soul of the powerful rulers settled in the bows/bunchuks and continued to protect their subjects, becoming a special spiritual protector of the people and the troops (legend about the soul of Chinggis Khan). Perhaps from here the loss of the battle banner was considered a great shame.

In the sources, the most common information is about the flags with the image of a wolf’s head (wolf – the oldest Turkic totem), here as a symbol of power.

The bunchuks, tugs and banners served as symbols of the tribe, military unit and the people as a whole. It is interesting to note that the banners were used not only in warlike conflicts, but also in sacred acts. Historians report that even in peacetime special marches were held to boost morale.

Kazakh ethnography is replete with references to the use of the banner in funeral ceremonies. For example, a white cloth was hung on the death of an elderly person, a black one for a man in the prime of his life, and a red one for a young man: White is a symbol of holiness, red is a symbol of youth, black represents great sorrow.The practice of worshipping sacred places and shamanic practices is an example of the use of tugs. N.S. Terletsky [14] notes that among the peoples of Central Asia, including the Kazakhs, drags were used not only in warlike conflicts, but also in funerary and memorial rites, in the veneration of the tombs of saints and nobles, and in the healing practices of the Baksy.

A.S. Bimendiyeva [15] points out the use of drags in wedding ceremonies, especially in the bride’s caravan on the way to the groom’s house. The great ritual significance of our ancestors was the sacral significance of the banner, which was the center of the path and was located on the border between the two worlds. These two worlds of the bride connect with the path of the wedding procession, which is guarded by the spirits of the ancestors. The way back is limited, the way forward is open and free [15, p.32]. The multifunctionality of the famous complex goes back to the understanding of the vertical staff (world tree) as a pillar of the world, a link between the earthly and heavenly spheres, a symbol of supreme power and an important cultic and ritual attribute. The ornamentation, color and shape of the banner carried a great semantic load in the banners.